Introduction

One of the first things humans do after birth is make a sound. In the womb, a foetus breathes the amniotic fluid in and out of its lungs as a preparation for breathing, but can not make a vocal sound until birth when air enters the lungs for the first time.

Breath can be seen in many cultures to have a spiritual significance – the Latin ‘spiritus’ means both spirit and breath, and inspiration means both breathing in and being intensely creative – and perhaps this is because of the way breathing so obviously extends from one part of life to another, perhaps because of the emotional quality of different types of breath – the sigh, the yawn, the suppressed gasp or sob, perhaps acknowledging the rhythms of breathing that accompany physical movement.

Along with breath comes voice, the activation of the vocal folds which are excited by breath passing between them, closing and opening in a precisely coordinated pattern to create a vocal sound that is as individual as a finger print.

At any rate, our voice accompanies us through life. A living, in-dwelling, changing musical instrument which can reflect our emotions, our age, our social status, gender, family origins, health and well-being. Voice helps maintain and enhance our social connection as we grow and develop and age. A voice for life.

Vocal warm-ups

Singing to warm up is not warming up any more than running to warm up for a marathon is warming up. Vocal warm ups are done to set the voice up for singing.

Although singing seems to me to be a human imperative – there doesn’t seem to be any human culture that does not involve singing – the vocal mechanism has other more important uses. To survive, humans need to be able to breathe, swallow and defecate - purely vegetative functions that take precedence over voicing in the great scheme of things. Singing seems to be a happy accident!

To warm up, it’s necessary to set up the body, breath and voice as a coordinated instrument. To build the instrument. Every time. It’s not sitting there waiting for someone to open the case and start playing.

Paying attention to the way we sit and stand is important. Everyone stands a bit differently, within the limitations of their age and stage.

Body, Breath, Voice, Tone, Range is one way of setting up. Examining and integrating the systems that sustain voice.

Body

Optimising body balance may involve bending forward to dangle the torso downwards, feeling a lower back stretch, and then rolling up slowly (bottom up). Or sending our awareness into our head, neck, shoulders, arms and hands, torso, hips and pelvis, legs, knees, ankles and feet (top down). Swinging from the waist, turning the head side to side gently and slowly and any other physical tuning in that the singer feels like doing - wiggling knees, shaking out hands, waggling the jaw, massaging the face, feeling for where the tension of the day is still holding on and gently releasing it.

Breath

Breath management is part of singing technique. The technique I use most is based on Accent Method breathing, a technique evolved to help stammerers, and then modified for singing.

Accent method breathing emphasises that the in-breath is a RELEASE, not a sucking-in of air. It locates the effort of exhaling in the muscles of the abdomen and de-emphasises the diaphragm.

The diaphragm muscle is an upside-down pudding basin structure that is connected to the ribs and the spine. Its function is to pull downwards on the lungs to inflate them. When singers exhale, the diaphragm muscle is relaxing, so ‘singing from the diaphragm’ is one of those traditional misdirections that can cause a problem if taken literally.

The muscles of the abdomen are largely responsible for creating the breath flow and breath pressure that singers use. There are four sets.

Transversus abdominus (TA) is the deepest one. It crosses the body horizontally, surrounding the abdominal contents, and is attached to the lumbar spine and lower ribs and pelvic floor, as well as directly to the diaphragm muscle.

The internal obliques are next – one set on each side - crossing the body diagonally from the rim of pelvic girdle to the lower ribs.

The external obliques cross in the opposite diagonal direction, originating from the lower ribs and attaching into the connective tissue that runs vertically down the abdomen and to the pelvis.

The rectus abdominis (RA) muscle is the well-known ‘six-pack’ muscle. It’s the most superficial of the four. Attached to the pelvic arch, this segmented muscle runs vertically up the body to the muscle junction at the base of the sternum bone (xiphoid process) and the cartilages of the 5th to 7th ribs.

The segmented nature of RA allows us to bend in the middle (isotonic contraction) and it can also be braced (isometric) for breath-holding and effort-making and stabilising the abdomen. The bracing movement might feel like ‘support’ but a tightly braced abdomen can close the vocal folds tightly against the pressure, creating pressure downwards. Bearing down. Singers don’t need to do this.

Accent method breathing emphasises the flexible movement inwards of the navel (isotonic) on exhalation, engagement at the waistband, and gentle engagement of pelvic floor muscles.

Unvoiced consonants – FF, SS, SShh, TThh (the soft sound in ‘think’) – are great sounds for breath exercises. These sounds can’t be made without significant exhalation. I use a pattern of four short sounds and one long one - F F F F FFFFFFFF for example, feeling for the excursion inwards of the navel. If the belly pushes OUT instead of moving in, just try being a little irritated (SH! Shushing someone assertively). Try shushing in a less irritated manner so the belly is soft, not bracing.

These four sounds can be voiced and then they turn into VV, ZZ, ZZhh and TTHH (the hard sound in ‘This’). Voicing the sounds means that you can use these sounds to

Sing glides over and octave up and down your range

Sing any other vocal exercise – arpeggios, staccatos, running note patterns

Sing a song

The sounds will help programme the music into your voice without your having to make vowel or consonant sounds, and they can be used as a cool down after singing as well. See later note.

Other warm up sounds – buzzes and hums

Humming, the siren (NG through your range), lip trills and rolled R can be used for musical voice warmup exercises without using a vowel.

Phonation through a wide straw (8 -10 mm wide) into a small amount of water can be another way of warming up. There are loads of videos online about how this works – maybe worth an internet trawl!

Troubleshooting breathing

Sometimes singers get asked to ‘squeeze the butt for the high notes’. This move can tend to turn on pelvic floor too much, and tighten the throat or lead to breath holding. Sometimes the instruction is to ‘inhale into the waistband’ but this move will engage the exhalatory breathing muscles for an inspiratory purpose and end up stiffening them.

‘Take a big breath’ can mean a singer ends up with unused breath and a high ‘clavicular’ chest setting. Instead of having enough breath, the singer can end up with stale, unexhaled air clogging up the works, so they feel out of breath. A good thing to do if you feel you are always out of breath is to stop, breath out, start again. Can you sing the phrase comfortably now? Maybe try getting a low breath. It won’t feel as full as a big chesty breath, but it will be far more comfortable for singing.

The problem with a nice low breath is that you don’t feel full up! But if you try it out and try trusting your body, you may find you have enough breath.

Your own sound

Try out a happy ‘hey!’, a sad ‘hey’, a bored ‘hey’, suspicious ‘ hey’. The way these sounds come out – motivated by an emotion, short and pithy and with an instinctive feel – is an indicator of your own vocal sound. You should sound like you. If your voice doesn’t match your age – sounds too old (or too young even!) – then maybe there is something getting in the way. You could be over-lowering your voice box by yawning to sing (an older singing idea that is not recommended these days) or holding your voice box too high and not accessing the fullness of your adult voice. Getting lessons from a good teacher can help you to get more comfortable with your own sound.

Vocal development

From infant to post puberty

Children are not just little adults (although it’s sometimes true that adults can be just big children!). The infant larynx, as illustrated in the slides, is very different from the adult one. It’s much higher up in the neck, sitting level with the jaw near the 3rd cervical vertebra. The thyroid (upper) cartilage is rounded, without the frontal prominence of an adult larynx (Adam’s apple), it’s right against the hyoid bone, and it’s tiny – about 12mm long and 18 mm wide (adult larynx is 40 – 50 mm in length and width). An infant’s vocal folds are 6-8mm long, growing to about 12-17 mm in women and 17-24 mm in men in adulthood

In infants, the tongue is much larger in the mouth by proportion to the relationship of tongue and mouth in adulthood. The throat area (pharynx) is smaller and shorter, the epiglottis (which closes over the vocal folds when humans swallow) is larger in proportion. The cartilages themselves (the larynx is made of 5 major cartilages) are altogether softer.

![]()

The vocal fold structure of the larynx is less well understood than that of the adult because examining it is invasive, but we understand that the structure of the infant vocal fold is simpler (3 layers) and less well-stratified than in adults (who have a 5-layer vocal fold structure).

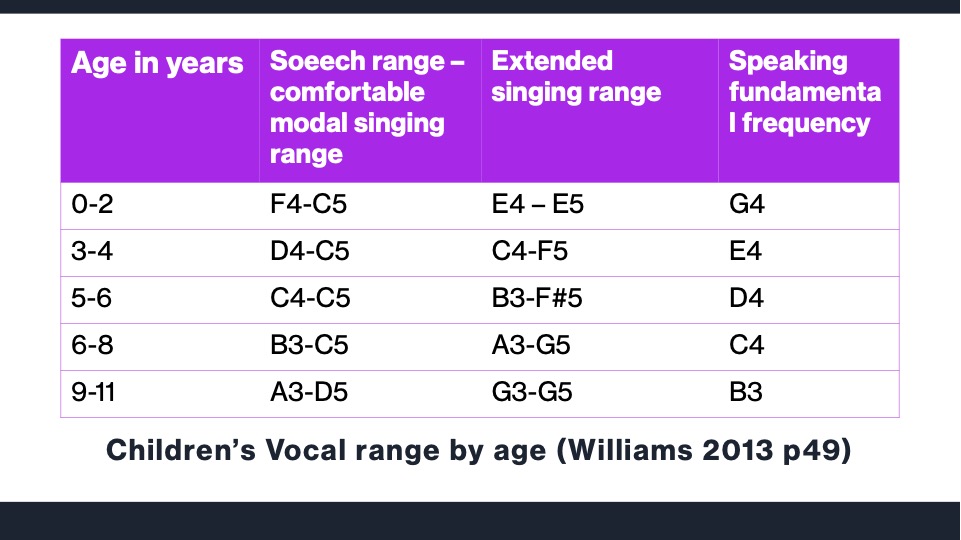

Age in years related to speech range, extended singing range and fundamental frequency

When a child passes through puberty, hormonal changes result in laryngeal changes. These are illustrated on the slides.

The voice and ageing

General body changes can and do affect the voice. Changes to joints and bone – arthritis and osteoporosis for example, can have an affect on the joints of the larynx, as can changes in muscle mass that happen as people age. In general, older men’s voices show an upward pitch trend resulting from this.

Older Women’s voices show a downward trend in pitch due to the effects of hormone changes at the menopause and there can be vocal dryness. The lower supply of oestrogen is largely responsible for this.

Reflux and digestive issues can have an effect on the voice. Acid and pepsin can cause inflammation in the throat if they spill over onto the vocal folds, and a cough associated with reflux can also cause irritation.

Some neurological conditions such as Parkinsonism can affect voice quality, resulting in a weaker-sounding voice, or result in a tremor in the voice.

But there are things we can do to maintain optimal vocal function as we age.

Singing lessons with a good teacher can help the singer optimise their technique. It may not recreate the sound of a young voice, but that is probably not a realistic aim anyway. The outcomes to look for are more ease, more confidence, more expressive depth, improved clarity. And most of all, enjoyment.

Choosing repertoire that the singer can invest themselves in, and which they are clearly capable of delivering is important. Whenever necessary, transpose to suit the singer. If you’re not auditioning for an opera, you don’t need to sing the aria you love in the original key (although transposing it more than about a minor third down is very likely to change the quality of the music too considerably and may indicate that the repertoire needs to change at this point). Singing a simpler song very very well is probably going to be more effective in performance than singing something complicated that taxes the singer’s resources to a considerable extent. All singers are different. The singer’s personality is always part of the equation.

There are songs older people sing that they may have learned in their younger days that now have a nuanced resonance and meaning they could not have had in youth.

Hearing those songs is a joy. Giving those performances might be scary for the performer because there is vulnerability in expressing the wisdom of a lifetime in song. As an adjudicator, I treasure these performances.

Useful resources

This is a Voice – Jeremy Fisher and Gillyanne Kayes

What Every Singer Needs to Know About the Body – Malde, Allen and Zeller

Teaching singing to children and young adults, second edition. Jenevora Williams

British Voice Association website – free resources on voice health, and lists of all the multidisciplinary voice clinics in the UK

Vocal Warm Ups app from Vocal Process – available free online.